J? On a Roman numeral?

What I’m going to say is partially redundant with the answer provided there. I like this topic though, so…

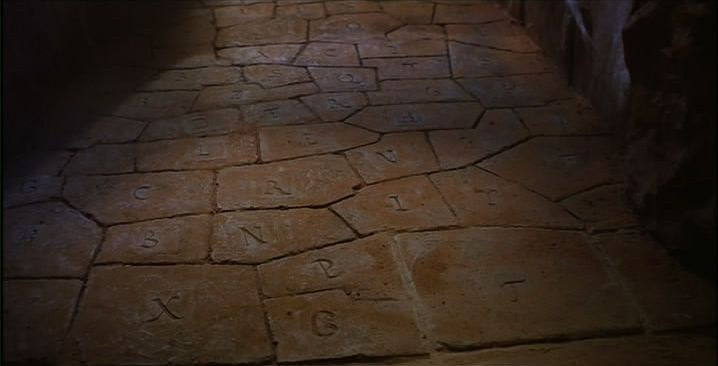

Another way to frame the same question would be what is the significance of making a longer ⟨i⟩ at the end of the number? Because that’s what that ⟨j⟩ is, a longer ⟨i⟩; since Roman numerals tend to use ⟨i⟩ a fair bit, that flourish was a visual cue that the number ended. That’s specially useful when you remember that the number will be found alongside text using the exact same letters. Like in this made up example:

- [without flourish] Vpon mashing together xxiii indigo floɯers, the resulting extract euaporated vnder sunlight for iii days.

- [with flourish] Vpon mashing together xxiij indigo floɯers, the resulting extract euaporated vnder sunlight for iij days.

It’s simply clearer this way.

It’s worth noting that ⟨J⟩ is not part of the Latin alphabet as used by the Romans. It started out as an allograph (same letter, written in a different way) of ⟨I⟩; so for example, writing “iust” or “just” would be the same thing, just like writing “banana” or “bɑnɑnɑ” with a fancy ⟨ɑ⟩ for ⟨a⟩. The main usage of this flourish was on word start/end, but specially in numbers, something that survived the ⟨I⟩ vs. ⟨J⟩ split (from 1500 or so).

You see something similar with ⟨U⟩ vs. ⟨V⟩, another rather recent letter. See on the example how I wrote “vpon” but “euaporated”? Bingo. I’m not sure if those allographs played any meaningful role with numbers though.

Addressing HN comments:

Seems Just like the letter -y at the end of a or Spanish (or English?) word is a glorified i, to make it more legible // Ley, rey, etc.

As the other user correctly highlighted, Spanish didn’t inherit Latin’s nominative forms (lex, rex, nox…); it inherited the accusative ones (legem→ley, regem→rey, noctem→noche).

The pronunciation of those words changed. And alongside it, the spelling. That Latin ⟨g⟩ in legem, regem used to be pronounced [g], like in English “gift” or “good”; but eventually it was softened to a [j], as in English “yes”. And the ending of the word was lost.

This wasn’t just Spanish, mind you, but pretty much all Western Romance languages. (Italian sometimes dropped it - cue to re, but legge). Then how you write that /j/ down is up to spelling conventions: Spanish picked ⟨y⟩, Galician ⟨i⟩ (rei, lei), and French went back and forth (in MF the spelling was still “roy, loy”, but nowadays “roi, loi”).

Edit: on the other hand, x used to be read /j/ (e.g. Quixote, Mexico), so also possibly lex —> lej —> ley

Spanish ⟨x⟩ used to be read /ʃ/, as in modern French and Portuguese. (It’s the first sound of “shampoo”). While ⟨j⟩ was used for the voiced counterpart, /ʒ/ (as in “Asia”) or /dʒ/ (as in “jeans”). Eventually both merged, got backed to the modern /x/ (as Scottish “loch”), and the resulting merge is now spelled with ⟨j⟩.

Jarmusch.